Are writers – through their contributions to popular culture – responsible for what seems to be a recent and growing divide between men and women? Has feminism’s attempt to right (and rewrite) a long history of injustice left men feeling a loss of status and sensing a threat to their identities?

It’s long been said – by Plato, among others – that art reflects society. Less often said, and less ancient, is the idea that art, literature in general, and fiction in particular shape society (e.g., Albrecht, 1954; Inglis, 1938). Both assertions have a feeling of truth, even if proof is elusive.

To set the social context, consider: In recent years, sociologists have examined the seemingly growing problem of young men having difficulty finding a place in society, for example, the problems of “involuntary celibates,” called “incels” in the trade (Sparks, Zidenberg, & Olver, 2022). In an extreme form, that manifests in them becoming mass murderers (e.g., Wood, Tanteckchi, & Keatley, 2024).

Six years ago, Helen Taylor (2019) published book about fiction and how women dominate the audience – as buyers and readers. “Overall sales for fiction books and e-books are 63 per cent female to 37 per cent male,” she reported.[1] The figures varied a lot by genre, but even so: In crime-thriller-adventure the spilt was close: 58 to 42 (for physical books; the ratio for ebooks was similar), but women still dominated. General fiction: 74 to 26 percent; Erotic: 71 to 29; Saga: 94 to 6. Since then, reports suggest that women dominate as new writers of fiction, not just as readers.

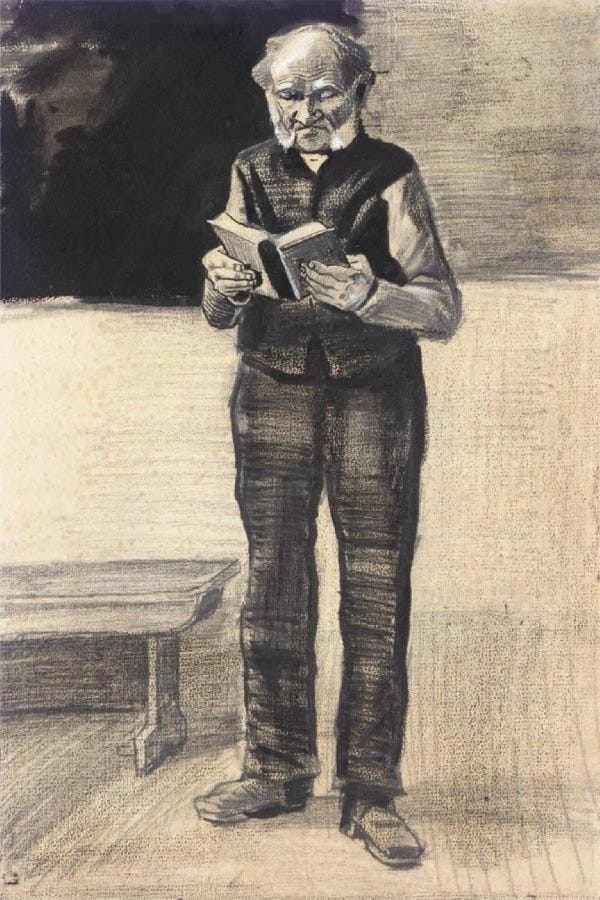

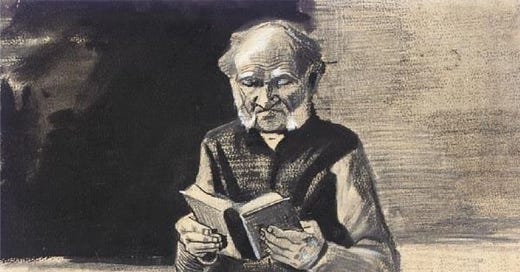

Taylor opens her study with an anecdote – an amusing (but unscientific) market research study conducted by the multiple prize-winning novelist Ian McEwan. McEwan and his son went to a park in London and handed out free copies of books. Several were from the Future Classics series published by Vintage. Others were books McEwan himself had written. Still others were several he had read and kept on his shelves. Within five minutes, thirty novels had found new homes, nearly all of them taken by women. Here’s McEwan’s account:

The guys were a different proposition. They frowned in suspicion … Reading groups, readings, breakdowns of book sales all tell the same story: when women stop reading, the novel will be dead. (McEwan, 2005)

This month, two decades after McEwan’s experiment, I thought about it again, prompted by hearing the former manager of the England national football team, Gareth Southgate, deliver a lecture to media executives and journalists assembled by the British Broadcasting Corp. Young men, he said, have been pushed to the fringes of society. According to Southgate, boys – not all, but many – have been pushed toward “callous, manipulative and toxic influencers” who trick them into thinking that success means money or dominance. He said:

Young men are suffering. They are feeling isolated. They’re grappling with their masculinity and with their broader place in society. … They spend more time online searching for direction and are falling into unhealthy alternatives like gaming, gambling and pornography. … And this void is filled by a new kind of role model who do not have their best interest at heart. These are callous, manipulative and toxic influencers, whose sole drive is for their own gain. They willingly trick young men into believing that success is measured by money or dominance, never showing emotion, and that the world – including women – is against them.

Southgate was a caring manager. He picked the players up when they were down, hugged the guys who missed penalty kicks that cost the team its chance of trophies.

The next morning, a female commentator on the radio observed that boys these days face a barrage of messages about how good girls are, what great opportunities they have. Girls score better on standardized tests. More girls than boys go to university. An even greater percentage of women than men leave university with degrees. No surprise, she said, that boys turn – in the darker corners of social media – to the siren songs of male fantasists.

Then, a day later, Thomas Tuchel, Southgate’s successor at the England team, named his first team selection for a qualifying match for the 2026 World Cup. News reports, including team member interviews, said that he had urged his squad to be more aggressive, to play closer to the line where fair play meets foul.

Six months ago, I wrote a post in these pages about a rush pieces of fiction – four TV crime series and a novel – where all, or nearly all, the male police were despicable characters, and the good cops were all women. At literary festivals where I live, most of the crime writers now seem to be women, too. Most of the young fiction writers of any genre are women.

Now this lands in my inbox: A writer named Jacob Savage wrote in the online magazine “Compact” an essay titled “The Vanishing White Male Writer.” It begins:

It’s easy enough to trace the decline of young white men in American letters—just browse The New York Times’s “Notable Fiction” list. In 2012 the Times included seven white American men under the age of 43 (the cut-off for a millennial today); in 2013 there were six, in 2014 there were six.

And then the doors shut.

In 2021, just one; none in 2022; one each in 2023 and 2024. There were no white male millennials in Vulture’s 2024 list, none in Vanity Fair’s, none in The Atlantic’s. The magazine Esquire, which targets millennial readers, has named 53 millennial writers among its yearend book lists as the ones to read since 2000. “Only one was a white American man,” Savage continued.

I may have stopped being a millennial about a millennium ago, but I am a white male born in America. I’ve read a fair number of novels in the past five years, quite a few by women. Only a couple were written by white males noticeably younger than me, guys who have a chance of making a name for themselves before the libraries send their books out to be pulped. Assuming the library even purchases one.

My little local library doesn’t have deep stacks housing the wealth of literature of the ages. It keeps the ones that people currently read. Looking at its shelves, my own (and unscientific) observations are:

That the fiction shelves – genre or literary – are full of books by women, for women, and probably about women.

That the second largest group of authors are those with two initials but no given names.

That there’s often a woman hiding behind those initials, maybe hoping not to put off the handful of male readers who, like me, still read fiction.

Or that, maybe, they are men hiding behind those initials in the hope that they won’t put off women readers who think the writer behind those initials is a woman.

Is the recent, and rightful, valorization of women in fiction – in print and on the screen – coming at the expense of male characters and thus contributing to the social isolation of boys and young men? And if so, with what damage, if any, on the social problems and mental health of boys and young men?

The trend toward female writers and readers of fiction may be bad news for men setting out on careers writing novels, but that’s always been a precarious occupation, for men or women. And it’s an economic problem for the writers, not a problem for society. Screenwriting is where the money is, and the competition there is even more fierce. Do men still dominate screenwriting? I suspect they do.

Taylor (2019, p. 6) notes: “Reading fiction can both transform and disrupt a life.” Is fiction in danger of transforming one category of lives while disrupting another?

There’s a research idea or two!

NB: The beginning of April sees the release of a new novel, @Gatsby, written by journalist Jan Crowther, and published (with a big splash, no doubt) by one of the Big Five, HarperCollins. It marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Her new book is set in contemporary America. Jay Gatsby this time is a woman, a social media mogul. The narrator, Nic Carraway, is also a woman. Let’s see what wonders the gender-flipping brings to this classic.

Albrecht, M. C. (1954). The Relationship of Literature and Society. American Journal of Sociology, 59(5), 425-436.

Inglis, R. A. (1938). An Objective Approach to the Relationship Between Fiction and Society. American Sociological Review, 3(4), 526-533. doi:10.2307/2083900

McEwan, I. (2005, September 20). Hello, would you like a free book? Contribution to TheGuardian.com. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/books/2005/sep/20/fiction.features11

Sparks, B., Zidenberg, A. M., & Olver, M. E. (2022). Involuntary Celibacy: A Review of Incel Ideology and Experiences with Dating, Rejection, and Associated Mental Health and Emotional Sequelae. Current Psychiatry Reports, 24(12), 731-740. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-022-01382-9

Taylor, H. (2019). Why Women Read Fiction: The Stories of Our Lives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wood, A., Tanteckchi, P., & Keatley, D. A. (2024). A Crime Script Analysis of Involuntary Celibate (INCEL) Mass Murderers. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 47(10), 1329-1341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610x.2022.2037630

[1] Full disclosure: Taylor is Emeritus Professor at the University of Exeter in England. As a “foolish, fond old man,” I studied creative writing there, but that was after she had retired and then published this book.

Thanks for this. Such a lot to take in. Will cogitate then get back to you. Can you say whether you have more replies to your pieces from men or women? I’m more likely to reply in person than via this little phone screen I have to use.

Cassandra