Old God’s Time – finally – comes

We’re familiar with the conventions of detective fiction. The investigator – on the force or off it, perhaps retired, perhaps just gone private – gets a knock of the door, maybe a phone call. Someone’s missing or dead. There’s a puzzle to solve – who dunnit? It’s an epistemological challenge – how do we know the truth beyond reasonable doubt? – and the hunt begins.

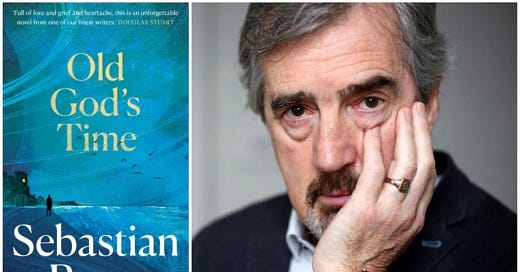

Sebastian Barry’s 2023 novel Old God’s Time starts out that way. But from the first few pages, paragraphs, sentences we know we’re in a different landscape, where those conventions don’t hold. But the language holds us nonetheless, willing us to get back to the comfort of a murder mystery or thriller, but not letting us get there, not quite, not soon. Here’s the first paragraph:

Sometime in the sixties old Mr Tomelty had put up an incongruous lean-to to his Victorian castle. It was a granny flat of modest size but with some nice touches befitting a putative relative. The carpentry at least was excellent and one wall was encased in something called “beauty board”, its veneer capturing light and mutating it into soft brown darknesses.

The next tells us that Tom Kettle now lives there with a few hundred books “still in their boxes” and with two old gun cases “from his army days.” It’s where Kettle has “washed up” – after a long time adrift in some as yet unspecified somewhere, we wonder? Or is it that he’s “washed up” in whatever occupation has occupied his time since the army?

After a brief survey of the landscape – an interior with a wicker chair and cigarillos, an exterior with a neighbor’s balcony sporting a gun rest, the sea close by, the boatmen “leaning into the oars” – comes the knock on the door, at the bottom of page two.

But the narrator, a voice deeply privy to Kettle’s mind, doesn’t let Kettle answer the door. Not yet. First we must learn of his daughter, Winnie, who “could never be said to disturb him,” not as the person or persons at the door had done, and of his son, not yet named but in New Mexico, “near the Arizona border” working as a doctor on “one of the pueblos.”

Then we learn that Mr. Tomelty is an efficient landlord, wealthy, perhaps an aristocrat, who owns a hotel here on the Irish coast, as well as the castle. But Mr. Tomelty spends his time with a wheelbarrow looking for weeds to ferry to his dunghill.

At the bottom of page three the knocking resumes. Then the doorbell rings. And again. Kettle finally pulls himself up from the wicker chair “as if answering some instinct of duty.” Perhaps now the mystery might begin.

And so it does. But not quickly. Kettle is a retired detective, having left the police nine months ago. The young men at the door are not – as the narrator first tells us – a pair the Mormons dressed in dark suits seeking to enlighten him. No, they are a couple of young policemen. They’ve come to see him, at the urging of the chief, about an old case, a cold case, and one that involved Kettle many years ago. Might he be able to help? It will be another 200 or so pages, maybe 50,000 beautiful words, before the narrator – and the mind of Kettle that voice occupies – let us even glimpse what the old, cold case might have been – or might still be.

No spoilers, then. There’s a murder to solve, though it will be a long and meandering path from here to the ending.

Had I been looking for the entertainment of detective fiction, I might have given up before the end of the first chapter. But this isn’t deep down just a story about a death, justice, or retribution, though it is all of those things. The prose tells me that – tells us that – from the outset, and it keeps telling us page after worm-like burrowing into the mind of this retired detective, into the story he clearly doesn’t want to tell us even as we learn, in fragments, how his family has rent itself asunder. From page 71:

In the early days she was as right as rain, wasn’t she? As right as Irish rain. And to him everything had been verging on the miraculous. He was so old, all of thirty, and he had long given up hopes of a deep love like that. And it was deep love. She was just a girl that worked in the Wimpy café in Dunleary. He and Billy Drury were down there for three long weeks trying to dig out evidence about a murder. Another girleen had been found murdered in a graveyard …

Then, page 141:

He hadn’t eaten and he wasn’t hungry, but he reckoned that, like an old wintering bear, he could get by on his fat for a night. But there was not peace now and maybe rightly. The nine months alone had been like a pregnancy, and it had given birth to new thoughts …

What propels this story forward is not the plot but the writing, the quiet metaphors, the leaps from one old thought to another, the lack of concentration. Something is about to be born but is taking its time – old god’s time – to come out, to allow itself to be said, admitted, made manifest in words in the “right as Irish rain” in February by the coast.

There’s something here about remembering but mainly about forgetting, about truth mislaid, suppressed, repressed, or wilfully set aside. The novel lets us dig into that mystery even as the narrator and protagonist push us – forgetfully, wilfully or something in between? – away from that expedition. Is this quest – this gradual stripping back of layers of forgetting, suppressing and outright lying – the equivalent in fiction of truth-seeking through archaeology (Foucault, 2005 [1966])?

Read this story slowly. The thin plot, as much as the tumble of words, the diversions and distractions, urges you to do that. We mustn’t rush to the end, because the end itself isn’t important, though it is the end. This is a story about how truth emerges only after a long gestation. Take your time with this story, old god’s time.

Foucault, M. (2005 [1966]). The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. London: Routledge.