Is journalism an enemy of the people, as Donald Trump declared shortly after becoming the US president in 2017? Or is it one of the institutions that keeps the power of leaders in check, the “fourth estate” of governance, as Edmund Burke (may have) said[1] to the British parliament in the late 18th century, a means of speaking truth to power?

And is it all right to lie to get to the truth?

Like a lot of people I know, I decided on a career in journalism because of the events of Watergate, and specifically by the work of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein at the Washington Post. I read their book, All the President’s Men, avidly, and watched the film version with Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman several times. Their stories led to the resignation, 50 years ago, on August 9, 1974, of Richard Nixon as president of the United States.

Like a lot of people I know, I saw it as a story of virtue defeating vice, and virtuosity in reporting defeating often vicious attempts to conceal the truth. Yes, the two reporters, outsiders to the main political beats of the bureau, needed to overcome the skepticism of their colleagues. But once they started breaking the news, the rest of the newsroom joined them in pursuit: Good vs. evil. Truth defeating lies. With an added dose of self-congratulation.

Journalism was a good thing to do: a moral craft through which I could also indulge in vanity.

Few journalism careers come anywhere near those of “Woodstein” and even theirs couldn’t repeat the excitement and impact of 1972-74. It was a dream we cherished, however. Was it an illusion? I’d like to think not, even now.

In our household, we recently watched two television series back-to-back, each dealing with wannabe Woodsteins, one set in Japan, the other in Finland. We’d watched the first season of “Tokyo Vice” a while ago and caught up with the second this time around, eighteen episodes in all. “Enemy of the People,” a 2022 six-parter, came on our screen almost as soon as we departed from Tokyo.

Much longer than the movie All the President’s Men, both stories play out much more slowly, the need for context greater, not to mention the need to read subtitles. Both have a supporting cast of journalists who were not a pure as those of the Washpost, and both with editors compromised by the crimes their underlings were trying to uncover.

Both are excellent yarns, bringing important corrupt practices to public attention. Both supporting casts have interesting bit parts, the varieties of crooks, con-men, and comrades. Both have protagonists who are personally ambitious, like Woodstein, back then, and as I longed to be.

And both protagonists are comfortable with lying as a way of getting to the truth. Unlike Woodstein, or I.

I’ll provide only a sketch of the plots. Let’s concentrate, though, on truth, and what it means for journalism and writing scripts about journalism.

Set in 1990s Japan, “Tokyo Vice” is a 2022-24 adaptation of a memoir by the real-life journalist Jake Adelstein, a kid from Missouri who learns Japanese, does well enough to become the first gaijin – outsider, not Japanese – to win a training post at a prestigious Japanese newspaper. His entry into the world of Tokyo crime reporting is the subject of the first season. The second sees him battle with a rumbling war between rival jazukus, gangs that run drugs and prostitutes. They also run protection rackets for the city’s many nightspots, including the hostess clubs in which exhausted Japanese executives buy excessively expensive alcohol in exchange for the chance to have long conversations with lovely young women, sex not included.

The complicity of the system – police, other authorities and even newspaper management – with the gangs seems to block every avenue of inquiry, presenting an even greater barriers than Woodstein encountered before the arrival of the source Deep Throat with his mantra: Follow the money.

But Adelstein makes up evidence, tells lies about knowing what he does not know, cannot find out, to put pressure of compromised crooks. The “good cop,” the relentless detective who befriends Adelstein in the first season and then overcomes even larger hurdles in the second, tolerates it, despite his moral objections. A world-weary Ken Watanabe, playing the role of Inspector Hiroto Katagiri, sums up this dilemma toward the end: “There is a time when the right choice is not the moral choice.” Right does not equal good.

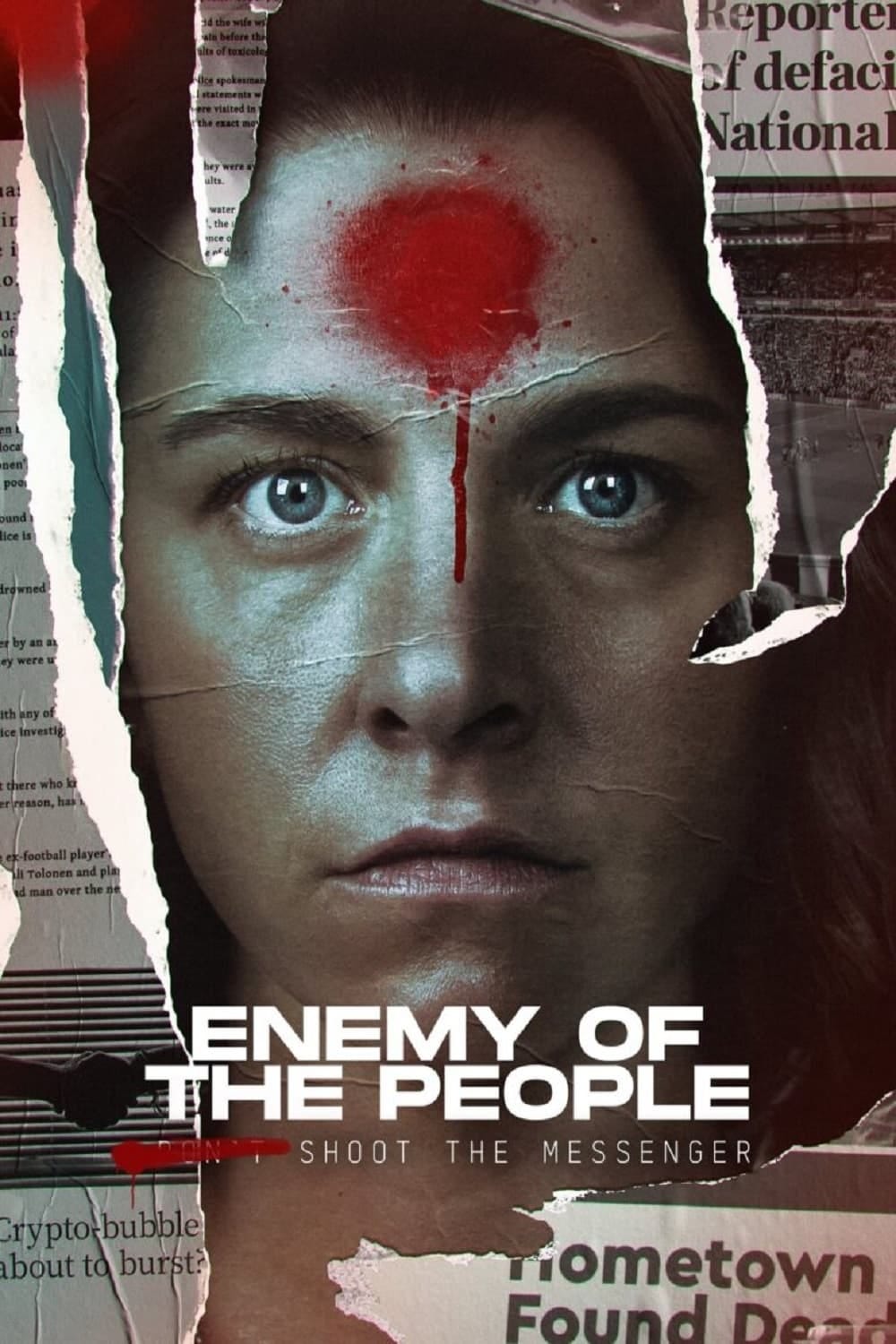

“Enemy of the People” is a more modest affair. Released in 2022, it tells of the death of a famous footballer, which arises from other, mainly financial crimes: misappropriation of funds, a cryptocurrency scam.

In the club-like world of this city, far from the capital, a seasoned reporter lands through some accident of fate, working for the local newspaper. Everyone in town knows everyone else, The mayor, a local construction company owner, the would-be crypto magnate, the footballer, the chief of police, and even the editor-in-chief of the newspaper are all chums. The obstacles in the way of truth are great. The reporter – like the gaijin Adelstein, like Woodstein – is an outsider. Like Adelstein, she is much more clever than other journalists, much more dogged in pursuit, and at ease with bluffing her way into crucial pieces of the puzzle, even threatening her version of “Deep Throat” into saying more – risking much more – than he has already.

Truth is a contested concept, philosophically. All the President’s Men, book and film, are based on real events, most of them reported in the pages of the Washington Post. “Tokyo Vice” is an adaptation – looser in the second season than the first – of the memoir of the same name. Looseness presents issues for truth. Facts blur into conjecture. “Enemy of the People” is fiction, but even fiction can point to underlying, epistemological, ontological, moral truths.

But the truths all three of these stories deal in are less contentious. They concern what happened, not why or with what significance or moral implications. Facts need to be established, that’s all, not the logic or theory that builds the truth-claim of more complex matters.

The title “Enemy of the People” is apposite, and not just for its resonance with the words of Donald Trump in 2017, or the fact that he’s running again for president, or that would-be Trumps in a growing number of countries around the world have proudly applied that label to their own news media. There’s another reason:

The 19th century Norwegian playwright Henrick Ibsen wrote a play called “An Enemy of the People.” His protagonist, Stockman, exclaims in Act IV: “All men who live upon lies must be exterminated like vermin!”[2] The news editor of the paper in the TV series speaks that line to her heroic but flawed reporter in the penultimate scene. It comes after (almost) everything is brought to light, after justice has (almost) been served, after good has (almost) triumphed over evil, after truth has (almost) vanquished lies. It’s the only time a link to Ibsen appears in the script.

Do the outcomes of these stories justify telling lies (even almost) in the pursuit of truth? Who are the vermin?

[1] Thomas Carlyle said it in 1840, of Burke’s parliamentary speech in 1771.

[2] As translated by Eleanor Marx-Aveling.

We loved Tokyo Vice and have just finished the third series when what is necessary to tell the truth becomes even more blurry. We haven't seen 'Enemy of the People' but will now look it up. I imagine it's a very narrow tightrope for journalists to walk sometimes. 'Lies, damn lies, and statistics' could easily be 'lies, damn lies, and journalism'. Should the truth have to be exaggerated/distorted to get a story? Possibly not. Should it be exaggerated/distorted so that people will understand its potential impact? Possibly.