Is Santa Claus coming to town? Is that a lie?

It’s Christmas time again, and the children’s books we’ve kept for the next generation of kids have found their way back to the top of the pile, into the hands of parents and grandparents, and from there into the eyes and ears of the youngsters. So far so Christmassy.

Then one day, in seasonal lack of good cheer, the news service called “The Conversation” produces a story with the headline: “Why you shouldn’t lie to your children about Father Christmas, according to philosophers.”

Philosophical spoilsports! Bah, humbug!

It’s penned by Joseph Millum from the philosophy department of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland to explain why we shouldn’t lie to children. Or rather, it’s re-penned by the journalists at “The Conversation” who regularly and often helpfully turn academic writing in something like news.

This one is based on an academic paper published in the Journal of Practical Ethics (Millum, 2024), which surveys philosophical thought and psychological research about the relationship between trust, lying and child development. Millum’s paper concludes:

Most parenting by lying—that is, lying to facilitate the day-to-day job of parenting—also appears unjustified. As a habit, there is some evidence that it is destructive to the parent-child relationship. It is a breach of trust. And it doesn’t set up children well to make good decisions.

“As a habit” is the operative phrase.

But two forms of lying seem to be justified. One is a lie that achieves a “legitimate moral aim” when no “morally better method” is available, like saying the park is closing, when it is not, for the sake of getting the child home for supper. The other is a lie that “really does protect the child” (Millum, 2024, p. 91). Here the boundaries are set, or approximated, by what it is not. The latter, Millum says, does not include lies that cover up, say, the fact of adoption.

Unlike the story in “The Conversation,” the body of the paper doesn’t use the word “Christmas.” Its focus is on lying more generally. At one point, however, Millum writes: “rather than repeating the myth of Santa Claus, a child’s parents might leave clues, such as ‘reindeer footprints’ or direct their kid to NORAD’s Santa tracker” (p. 75). It’s a way of dodging the outright “lie.”

But wait a second! Don’t we tell children lies all the time? Another book we pull off the shelf is Dr. Seuss’s The Grinch Who Stole Christmas. Is there really a danger that the three-year-old believes in the Grinch? With the next book, does the child believe in “green eggs and ham”? Are those all lies?

Indeed, isn’t every piece of fiction a similar form of lying, an attempt to persuade readers of a reality different from the day-to-day one? In doing so, it’s a piece of make-believe, an exercise of imagination, of the writer and reader and not-yet reader, if not quite alike for all three. Making believe isn’t quite the same thing as lying. Isn’t the question whether parents perpetuate myth as fact, rather than showing that storytelling can convey a different sort of truth.

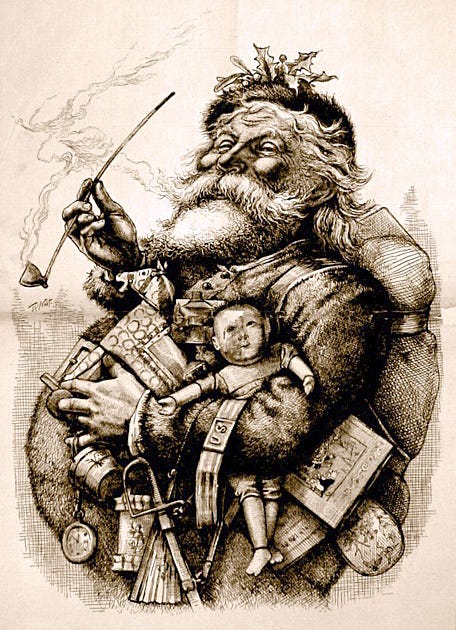

Perhaps the “habit” we need to cultivate is telling stories with the same sort of twinkle we imagine in Santa’s eyes.

Postscript: About the time I published this post, “The Conversation” published a rebuttal of its original one, based on Millum’s paper. In it, Tom Whyman, a University of Liverpool philosopher, makes the case for lying about Santa.

As we’re growing up, we probably do on some level need to believe that the world is good and just: the sort of place where a jolly man runs a workshop staffed by elves, rewarding the nice children and (lightly) punishing the naughty.

If not, would youngsters really find it in themselves to fight for a better world?

And when should parent abandon the story?

Parents should surely maintain the myth while their children remain small, but answer honestly when confronted directly. When a child finally asks, at the age of six or seven, “is Santa real?” – that’s when they no longer need the noble lie.

Merry Christmas to all, then! Including you, Santa!

Millum, J. (2024). Lying To Our Children. Journal of Practical Ethics, 11(2). doi:10.3998/jpe.6215