The roots of any crime series always lie in what’s gone before. Some are mere copies of little distinction but decent entertainment – whether in novels, television or movies. Others, however, do what philosophers say of each other: They “stand on the shoulders of giants” (Merton, 1965/1985). That doesn’t make a story great, of course, just in a position to see and show something others haven’t.

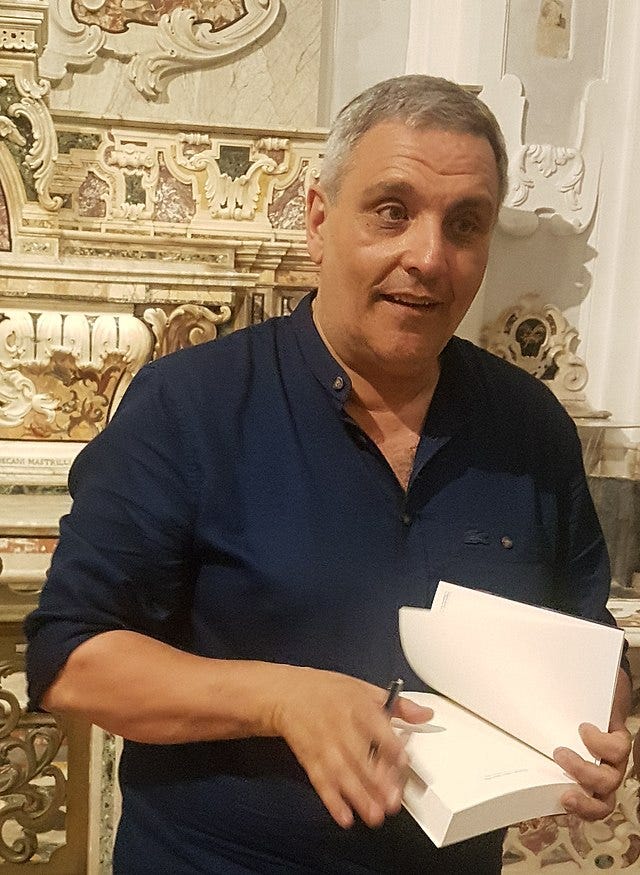

Part way into this television series, based on the novels Maurizio De Giovanni, I think I’m watching one of the latter.

“Il Commissario Ricciardi” investigates a series of murders in 1930s Naples, each single crime solved in a single, two-hour episode. Ricciardi uses dogged attention to detail to construct a picture that leads to a confession. A uniformed police sergeant plays a vital role. His working-class background provides access to sources different from those the suave, serious detective encounters. Together, their pincer approach squeezes out facts from unwilling informants until the perpetrator can be unmasked. So far, so ordinary.

But differences unfold steadily – and they distinguish this program from the rest. Each crime points to an underlying, deep-seated problem in the social structure, creating barriers to truth. And the nature of truth lies at the heart of any detective story worth the time it takes to write, read or view, as many literary theorists have discussed (Bowker, 2021; Jameson, 2017; Marcus, 2003).

To get to the truth, Ricciardi sees apparitions at crime scenes, blurred images in corners, chanting what (a little detective work by viewers watching subtitles will show) may be lines from old Neapolitan proverbs but also the last words of the victims – ambiguous clues that tantalize but don’t solve the mystery. This is a ghost story, yes, but not just.

The sergeant, too, has a secret source for detection, a drag queen, living in a squalid alley of more ordinary prostitutes. He knows everyone and everything that happens when the low-life citizens of the city come in contact with its those from its upper echelons.

Gimmicks? Probably, but drawn with skill. A viewer may embrace their implausibility without having to buy into the light-hearted, even light-headed metaphysics.

Ricciardi himself is an enigma. Unsmiling, sad but radiating a warmth that everyone can see. Piece by piece, each episode gradually reveals his background: a beautiful mother who dies when her son is just teenaged. After her death comes an education in a boarding school. A few episodes in, we learn that he is a nobleman, a baron. Ricciardi is a man who seems to own a large estate somewhere in the country but chooses to ignore it and live in an apartment in Naples with only a housekeeper for company, the elderly woman who was his nanny from birth. But we are still to learn about his father.

Using aristocrats as detectives to heighten the interpersonal drama between detective and sidekick is a device we know from, among others, the Inspector Lynley Mysteries, a British television series from the early 2000s, much adapted to good if not great effect from the novels of the American crime writer Elizabeth George.

But in this series, we feast on the elegant interiors of Naples, the high ceilings, the solid stonework of both public and private buildings, standing in stark contrast to the and the dismal, narrow streets of the slums of Naples during the height of the Great Depression. Even the quiet views across the harbor and bay carry and omen: Mount Vesuvio steams in the distance, ready to erupt at any time.

And it’s the 1930s, the depth of the Great Depression, and the height Fascist power. Italians may still respect, even honor their aristocrats, but they fear their rulers. In the first episode, only a portrait of Mussolini hanging behind the desk of the deputy chief of police signals this theme, a context-setting background device. But a few episodes later, the black shirts are a part of the story itself, and the direct threat to the “dissident” coroner, and even to the aristocratic detective, begin to move context into the foreground.

These plots may be solved implausibly through the intervention of ghosts and gossip. They leave viewers with the sense not that they are real, but precisely that they are not. Reality was not then, is not now, full of such beautiful imperfections. Still, we’re pulled in by the slow pace as each layer of society unfolds, some enchanting, others ugly, and as love worms its way into Ricciardi’s life and worries. This series makes a pleasant break from the standard, routinized, relentless flow of crime dramas trying to outdo each other with gore.

In our household, we felt all the pleasure of watching that other glorious and picturesque detective series, “Il Commissario Montalbano,” based on the novels of Andrea Camilleri. That one uses the Mafia was a persistent backdrop, but one that only occasionally pushes its way to the front.

Like “Montalbano,” the “Ricciardi” series has a quiet, humorous side to its stories. But in contrast to it, these stories make us smile despite the bittersweet plots, sad characters and the growing menace of the political setting.

Bowker, M. (2021). Truth in Fiction, Underdetermination, and the Experience of Actuality. The British Journal of Aesthetics, Online first. doi:10.1093/aesthj/ayaa036

Jameson, F. (2017). Raymond Chandler: The Detections of Totality. London: Verso.

Marcus, L. (2003). Detection and literary fiction. In M. Priestman (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction (pp. 245-268). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Merton, R. K. (1965/1985). On the Shoulders of Giants: A Shandean Postscript. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.