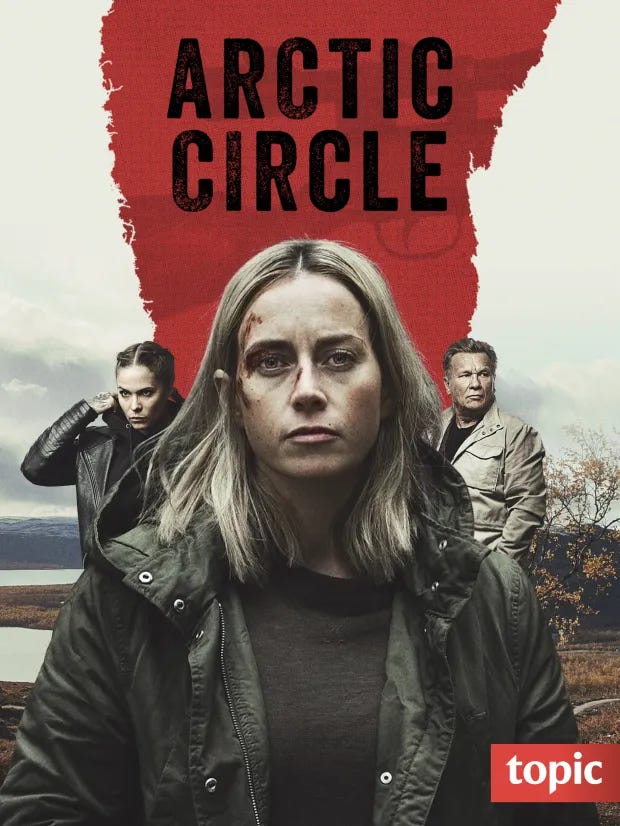

In 'Arctic Circle' the manifestly untrue feels real

A couple of years ago, we spent twelve hours with a riveting series called “Ivalo” that features police cooperation across the border between Finland and Russia inside the Arctic Circle.

Cooperation? Across that border? The show was conceived and filmed well before either country thought Finland would ever join NATO. This is fiction, though, not true crime, so let’s imagine a fictive Russia and Finland, and happier days, when the Finns were merely wary of the Russians and the Russians merely arrogant, not hostile.

Ten of those hours were with the first season of “Ivalo,” called “Arctic Circle” in translation. The other two hours came from the second season. I can’t remember why we didn’t watch the rest. Did we forget about it, somehow, or just get distracted. Season 1 (2018) told a story of mainly domestic concerns – the death of prostitutes working across a border so distant from the attention of authorities in Helsinki or Moscow that no one would see it as a place worth worrying about, for drug trafficking, people smuggling, or other crimes. Season 2 (2021-22) picked up where the first left off. Perhaps we’d had enough.

But we came back to Season 2 recently. We re-watched the first two episodes and sensed the approach of a change of direction. By episode 3, we were hooked by accumulating, scattered facts.

A secret society of the wealthy from around the world occupies an abandoned monastery deep in the forest in the utmost north-western corner of Russia. The monastery has been purged from all the maps of the area, as secret military installations are. It’s as if the building had never existed. A Finnish ice hockey professional disappears, a man widely thought to have killed his girlfriend, a promising judo Olympian, twelve years before. Then one of the characters from the first season, a Russian prostitute who was granted Finnish citizenship and moved south, is found shot in the head when returning by train to Ivalo, the Finnish bordertown inside the Arctic Circle.

These seemingly isolated events are not unconnected, though. This is fiction, after all. And the protagonist, in both seasons – a Finnish detective who lives with her daughter, a charming Downs Syndrome child – feels the connection that facts cannot substantiate. It’s not even a theory. She strikes up a collaboration with a Russian detective, forcibly exiled from St. Petersburg to the Arctic town of Murmansk. They set off to investigate the anomalies and the fragments of evidence, and – of course – discover the truth. I won’t spoil your enjoyment by disclosing more of the plot.

What’s intriguing about this frankly preposterous story is the writing, how all the personal digressions, the backstories of the characters, the connections to family and friends, combine to create something believable. It’s one of the tricks of fiction – that something manifestly untrue can become real in the minds of the audience. It can reveal truths we would ordinarily never see from sticking to the facts.

Take the daughter: Her interactions with all the other characters are touchingly human. That she is the person who discovers the prostitute on the train with a bullet in her head tells us without saying so about the vulnerability of children to violence. It reminds us that we adults, we television viewers, shouldn’t accept this, either, however inured we may be with violence in television shows and the prevalence of vile actions in so many of the things that keep us glued to the box. It sensitizes us to see other such reminders floating in the background of the hunt-and-chase of crime writing.

In all its preposterous storytelling, Season 2 makes us constantly question why we put up with the horrors. Why can’t we just all get along?[1]

There are some parallels to an earlier cross-border drama “Bordertown,” set in the south of Finland, including the tentative and strained relations between police on each side. Both were conceived and filmed before Russia invaded Ukraine and Finland sought refuge by dropping its notional neutrality to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. A third series of Arctic Circle aired in Finland in the autumn of 2023. Surely those events complicate further the cross-border collaboration that underpinned the first two series. I’ll be looking out for it when it comes out where we live.

[1] The line is from Rodney King, whose 1992 beating by police in Los Angeles sparked riots. King appeared on television and spoke these words to try to defuse the tension. As later events showed, his words may be remembered now more for the effect they failed to have than for the meaning he tried to project.