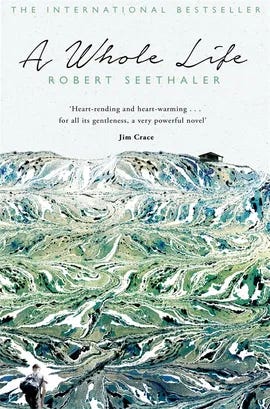

A Whole Life, in a few words: Robert Seethaler

Somewhere I came across a reference to the Austrian novelist Robert Seethaler. It said he had written one of the best short novels of the recent past, one you might read on a single, lazy afternoon. I wasn’t familiar with the novelist or the book, but my library was. The book is Ein ganzes Leben (2014). The 2015 English translation, A Whole Life (a sensitive rendering by Charlotte Collins) was shortlisted for the Booker International prize the following year. One-hundred fifty pages with fewer than two-hundred fifty words to a page. That’s less than forty thousand words.

If a “whole life” can be told in that small a book, then it must be a life in which little happened.

And so it was.

But told with such poignance! The book deserves the accolades on the back cover from British newspapers: “quiet, concentrated attention” (Sunday Times), “magically captures the universal (Daily Mail), “Genuine wisdom and restrained poetry” (Sunday Telegraph). You read it, and you know you’ve found something remarkable, yes.

But what in the writing, what marks on the page, make it remarkable?

Let’s start with a brief description of the (lack of) story, the unremarkable events that tell the story of a man, Andreas Egger, living mainly alone and mainly in a village in the Alps. He lives a long time – from the very late 19th century to the 1970s, through two world wars, the Great Depression and the rise of the Nazis, the economic and political dynamism of the post-war period. And then he dies.

An orphan, Egger has suffered under the abuse of Kranzstocker, an uncle by marriage, who has reluctantly taken him in. We see only a small but important example: The beating leaves young Andreas crippled. The broken leg heals out of place. He limps forever.

One day, having grown strong through manual labor on the farm, he defies Kranzstocker and leaves.

Once Egger falls in love. He marries the woman. She dies in an avalanche in his house while he was outside trying to trace the source of strange noises he has heard in the night.

Once, on the eastern front in the Second World War, he single-handedly defends the frontline. Not a shot is fired, at least not where he is stationed. Having run out of food he returns, against orders, to find his base camp occupied by the Soviet Red Army.

Once imprisoned by the Soviets, he remains so for several years after the war ends, he eventually returns home, where almost nothing happens.

Once, he takes a bus ride to the end of the line. And then returns on the same bus.

As an elderly man, he once has a disagreement with schoolteacher about noise, which turns into a single-night liaison. They separate.

The events might lead a different novelist to pen a thousand pages describing love and lovemaking, conflict and incarceration, elaborating the experiences and the meanings of love and war, of war and peace, of the bonds and wounds of relationship between the people in a village as it develops from a precarious outpost of human existence to a ski resort. This is stuff for a Tolstoy. Seethaler pulls this off in less than a tenth as many words. How does he do it?

Writing in the weekly newspaper Die Zeit, the German critic Iris Radisch describes his way of writing as being in the manner of baking a “true German rye bread, without artificial raising agents or aromatics” (cited in Wisotzki, 2021, p. 173).[1] Let’s examine the text to identify some of the devices Seethaler uses, using one example of each:

Time

The book begins in 1933, when Egger is possibly 35 years old. No one knows for sure. His birth date was selected randomly, assigned by a bureaucrat some months or years after the date.

The time soon shifts – to Egger’s childhood, the beating, then to his old age and his quiet disorientation to village of the 1970s. Then back. We see the whole life sketched in just a handful of pages. The timeline will shift again, several times, as those thin lines of the sketch thicken. What these fluid time-shifts develop is repeated layers depicting the constancy of character, stoicism and puzzlement through this whole life.

Diction

The opening of the story relates how Egger tries to carry an aged recluse – nicknamed Horned Hannes – from his hut high up the mountain down to the village as a snowstorm threatens them both. Carrying Hannes hitched on a makeshift rack his back, Egger slips and tumbles twenty meters down the mountain, stopped only by crashing into a boulder. Lying in a heap in the snow, they engage is this concrete yet metaphysical dialogue:

Hannes: People say death brings forth new life, but people are stupider than the stupidest nanny goat. I say death brings forth nothing at all! Death is the Cold Lady.

Egger: The … what?

Hannes: The Cold Lady…. She walks on the mountain and steals through the valley…. She seizes you as she passes and takes you with her and sticks you in some hole. And in the last patch of sky you see before they finally shovel the earth in over you she reappears and breathes on you. And all that’s left for you then is darkness. And the cold.

Through “clenched teeth,” Egger mutters: Jesus. That’s bad.

“Neither man stirred again,” the narrator continues, until Hannes escapes from the harness and bounds into the blizzard and back up the mountain, out of sight before Egger can get onto his feet.

This dialogue – like the language of the narrator, its choice of words narrow and ordinary – evokes the bleakness of two solitary lives, ones that are nonetheless connected. Until they are separated. Unless they aren’t. And toward the end of the book Hannes reappears.

Rhythm

Speak this passage aloud, narrated as Egger is rounding out his whole life. Listen to its flow:

In his final years Egger did not take up any more offers of work, which in any case became increasingly infrequent. He felt that in his life he had toiled enough; besides, he found the tourist chatter and their moods, which changed as constantly as the mountain weather, increasingly hard to tolerate.

Both sentences begin with short declarations of fact, followed by increasingly looping abstractions. Those abstractions use only simple words, but they evoke more abstract concepts, ones those words have accumulated through the telling of the tale.

Punches pulled

The point where the book begins – 1933 – is the year another Austrian, a World War One veteran with a modest military background and about the same age as Egger, seizes power as Chancellor of Germany. Seethaler doesn’t mention Adolf Hitler until half-way through the book, however, and then only obliquely. When war comes six years later, Egger volunteers to join the army, but he is turned down because of age and disability. Only to be drafted to fight a year later and sent to the bloody Eastern front. We feel the punches Seethaler hasn’t thrown.

This device, too, recurs in various forms throughout the storytelling. It builds layer upon layer of meaning as the unfamiliar but immediate context draws in the familiar but distant and unspoken context.

From simple writing: ontology, epistemology, ethics

What these devices do leads us to think about – or perhaps to feel – the narrow world that this character inhabits as whole, just as his life is whole, unified and comprehensible. But it sits within a wider world, mentioned only in passing, but one that we, the readers, know better than the protagonist can. It lets us think about – and feel – what happens in the ordinary world we inhabit and experience as whole. Maybe it too sits within the larger whole. As I read this short novel – twice – I found myself thinking, no, reliving incidents of the wars during my lifetime – Vietnam, Kuwait, now Ukraine – and of the loves I have lived and lost.

Seethaler’s slender selection of facts tells us only what we can know; he shows, tangentially, through shifts of time, diction, rhythm and the punches not thrown, what we might know but only in part, that is, what might be true.

He gives us a character, however, who acts and makes choices about those actions, while offering only glimpses of any rationale or motivation for those decisions. Still, we come away feeling that this is – at heart, in substance, the stance below the surface – a good man.

In her doctoral dissertation, called in English translation “The Art of Simplicity”, Wisotzki (2021) analyses Seethaler’s works alongside other contemporary authors writing in German. “Art” is, though, close but simplified translation of her original Kunst. Simple language, combined with rhythm, evoke ambiguity and build for readers a complex understanding of the world the writer portrays.

Simplicity. It’s a disembodied abstraction. The original German word, Einfachheit, is a property of a person. It might be better called the state of being simple, or simpleness. This simple form of writing is what creates the complexity of understanding. It does so economically, if what we’re counting is just the number of words. But it is not economical in the questions it asks its readers to ask themselves. Read for yourself.

Wisotzki, N. (2021). Die Kunst der Einfachheit: Standortbestimmungen in der deutschen Gegenwartsliteratur. Judith Hermann - Peter Stamm - Robert Seethaler. Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript Verlag. http://doi.org/10.1515/9783839458327

[1] My translation. Radisch’s original contains a richly textured ambiguity that sadly can’t be translated directly. The German is this: die Schreibweise nach Art des ehrlichen deutschen Roggenbrots ohne künstliche Triebmittel [sic] und Aromastoffe, in which the German Art means “manner” (but can mean artistry), künstlich here means “artificial” (but with echoes of “artistic”), and Treibmittel is the i1ngredient (yeast or other) that fills the dough with warm air. Who says German is a coarse, unsubtle language! (NB: Witsotzki’s text reverses the vowels in the word Treibmittel.)