A stage adaptation of George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four is touring in Britain. I saw it recently at one of its regional stops.[1] Decades ago, in the depths of the Cold War, I read the novel. It seemed then an allegory of the Soviet Union, as it probably did when Orwell was writing it in 1948.

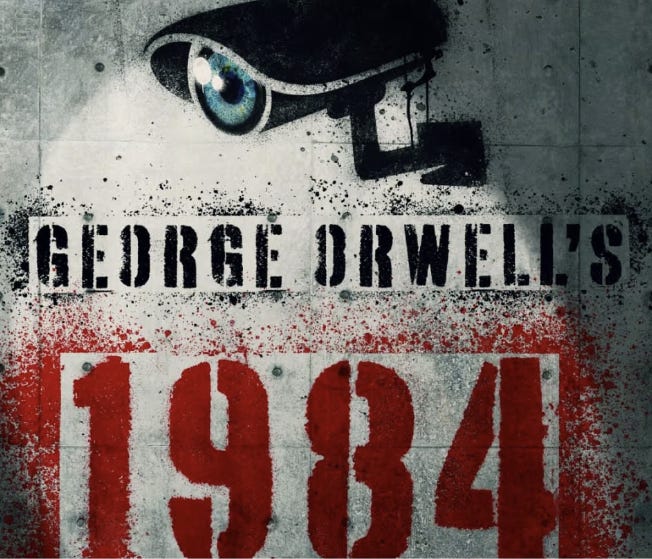

Orwell’s creation of a new vocabulary – and the concept of exerting control over the minds of the population by systematically shrinking that vocabulary – was a revelation, e.g., in its “Newspeak”: +good, ++good. Its “Big Brother” became a household word, and eventually the title of a so-called “reality TV” version of a so-called “safe” form of cruelty.

There’s nothing “safe” about Ryan Craig’s adaptation in 2024, however.

First, the far-right in European politics is celebrating electoral breakthroughs in the Netherlands and Austria and upsetting political order in Spain and France. Russia is two years into its attempt to subdue Ukraine. The US presidential election campaign in entering its final month, with constant reminders of Donald Trump’s term in office (2017-2021), and its reliance on “alternative facts,” the words used by his strategist Kellyanne Conway at the very start of the administration. It was a clear echo of Orwell that tried to drown out the warning he had tried to deliver.

Second, the play version is even more wrenching than the novel. Text on a page – even from the typewriter of a master like Orwell – is much less visceral than what we see on stage. The audience has been forewarned: “Contains scenes which some audience members might find distressing, nudity (male) and full blackout.” But those scenes still come as a shock.

The story of Orwell’s book, and the play, is set in “Oceania,” a country at war. The enemy changes as the book develops. The foe is “East Asia” in the early parts, then “Eurasia” in the later parts. That could be the Soviet Union, sitting between Japan or China on one side and the alliance of western Europe and America on the other. But many critics interpret Oceania as Britain, which – in 1948 – was just shedding its empire that had spanned the globe during the previous two centuries. The aging Great Power then found itself trapped between two superpowers – the Soviet Union and America – both challenging Britain’s old class-driven order. The protagonist is very English: “Winston Smith.” His mentor (and nemesis) is Irish: “O’Brien.”

And this: Is there a war at all, or is “war” the excuse a failing “party” – there’s no mention of “government” – gives for the hardships it inflicts on the population? These things we’ve understood for decades.

Orwell’s book also anticipated control of populations through ubiquitous technology. The omnipresent screens that provide surveillance (exceptionally well presented in this staging!) may have been superseded in contemporary life by smart phones and watches. But how can we – we readers, we audience members – not realize the menace they present?

So why write about it, now, again?

Because Nineteen Eighty-Four isn’t just a rebuke to politics or technology. Orwell’s other target was philosophy. A central theme of the novel and the play is truth, or what passes for it. (A second is freedom, which I may discuss in a later post.) Orwell mounted a passionate defense of truth. His most central attack is against ontological and moral relativism, so prevalent in the philosophy that developed from Heidegger (1927/2010) through to postmodernism. Orwell may start with an attack on “alternative facts,” but it continues beyond that. This is the tragedy of a man – Winston Smith – whose given name recalls Churchill and surname connotes everyman.

But his attack relies on a commonsensical understanding of truth, alien to what Heidegger and the postmodernists and poststructuralists – including Michel Foucault (1975, 1979) and his version of surveillance and punishment – tried to articulate. They saw instead a complex interaction of sensory data, interpretive perception of those data, and theoretical understanding that develops through interpretation.

And it wasn’t just these “continental” philosophers. In 1948 as now, physics itself – the fundament of natural sciences – has pointed us to the shortcomings of common sense:

Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle,

Schrödinger’s perception-sensitive reality,

the probability-dependent ontology of quantum mechanics.

Things should be as simple as possible, and no simpler, as Einstein might have said, but probably didn’t, quite.

The book and play seek a simpler idea of reality than the one philosophy was seeking to articulate. Orwell sought a return to a world in which truth is not historically and contextually contingent, as it is in the pragmatism of William James (1907/1955), but instead objective and manifest for all to see. This kind of truth feels right, in the sense of most like what we think we know from daily life, and in Nineteen Eighty-Four it feels right, too, in a moral sense. But is it?

Which brings us back to politics, the novel, the play, and 2024. Even if “truth” is complex and difficult to discern, surely there’s more than the “anything goes” of the simple and simplistic relativism against which Orwell warns.

Every year, the National Football League’s Superbowl is the most watched event in American television. During the one in January 1984, Apple Computer Inc. ran a commercial. It was directed by Ridley Scott, who had recently directed the movies “Alien” (1979) and “Blade Runner” (1982), a one-minute spot, and at the time the most expensive commercial ever, so costly that the Apple board thought it threatened the company’s existence. Its target was Apple’s opponent: IBM, the biggest maker of the then-ubiquitous mainframe computers and a recent entrant in personal computing. IBM was Big Brother. The intense and unvoiced commercial resolved into a single frame of text that launched its very first Macintosh computer: “you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984’.”

In 2024 we are witnessing uncommon challenges to our sense of right and wrong, in politics, war, misinformation, and disinformation. We’re seeing the technology of Apple and all the other tech firms provide a basis for the distortion of truth – whatever that means – for political ends and in a complexity that even Orwell – as prescient as he was – could not have imagined.

We can hope, can’t we?, that 2024 doesn’t have to be Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Foucault, M. (1975). Surveiller et punir: Naissance de la prison. Paris: Gallimard.

Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). London: Penguin.

Heidegger, M. (1927/2010). Being and Time (J. Stambaugh, Trans.). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

James, W. (1907/1955). Pragmatism: A New Name For Some Old Ways of Thinking – Popular Lectures On Philosophy. New York: Meridian Books.

[1] It was playing at Lighthouse, a wonderful, wonder-filled performing arts complex in Poole, on whose board I have served for six years.

Excellent review of 1984, the play and the book, and the overview of their implications. I am struck especially by the hope that Truth is possible to find, whatever Truth may be [as you suggest]. Something else keeps occurring to me in any discussion of the fascism and repression of freedom of thought implied in all this: Human Nature. What role does this complicated Truth play? Philip Roth, in his Plot Against America, offers terrifyingly blunt perspective of human nature when he has the mother of the family at the book's center speak in simple yet profound terms: "Just watch what people do when they realize what they can get away with." Thanks for this great entry, Don.